Kim Brown Seely

Writer. Mariner. Coffee-drinker. Leaver-of-town.

Writer. Mariner. Coffee-drinker. Leaver-of-town.

Virtuoso Life, Nov/Dec 2008. Photography by Michael Nolan.

THE WIND WAS THE DISTILLATION OF COLD ITSELF. It shrieked down the ice-covered basalt cliffs, ripped across the bay, and shredded the rocky spit where I stood with a dozen other red-parka-clad travelers. Moments before, a Zodiac had dropped us off for a rare landing at Antarctica's Elephant Island. We'd scrambled ashore, thrilled to set foot upon the aptly named Point Wild, the legendary beach where Sir Ernest Shackleton's Antarctic expedition had survived - on penguins and seals -for an unthinkable 137 days.

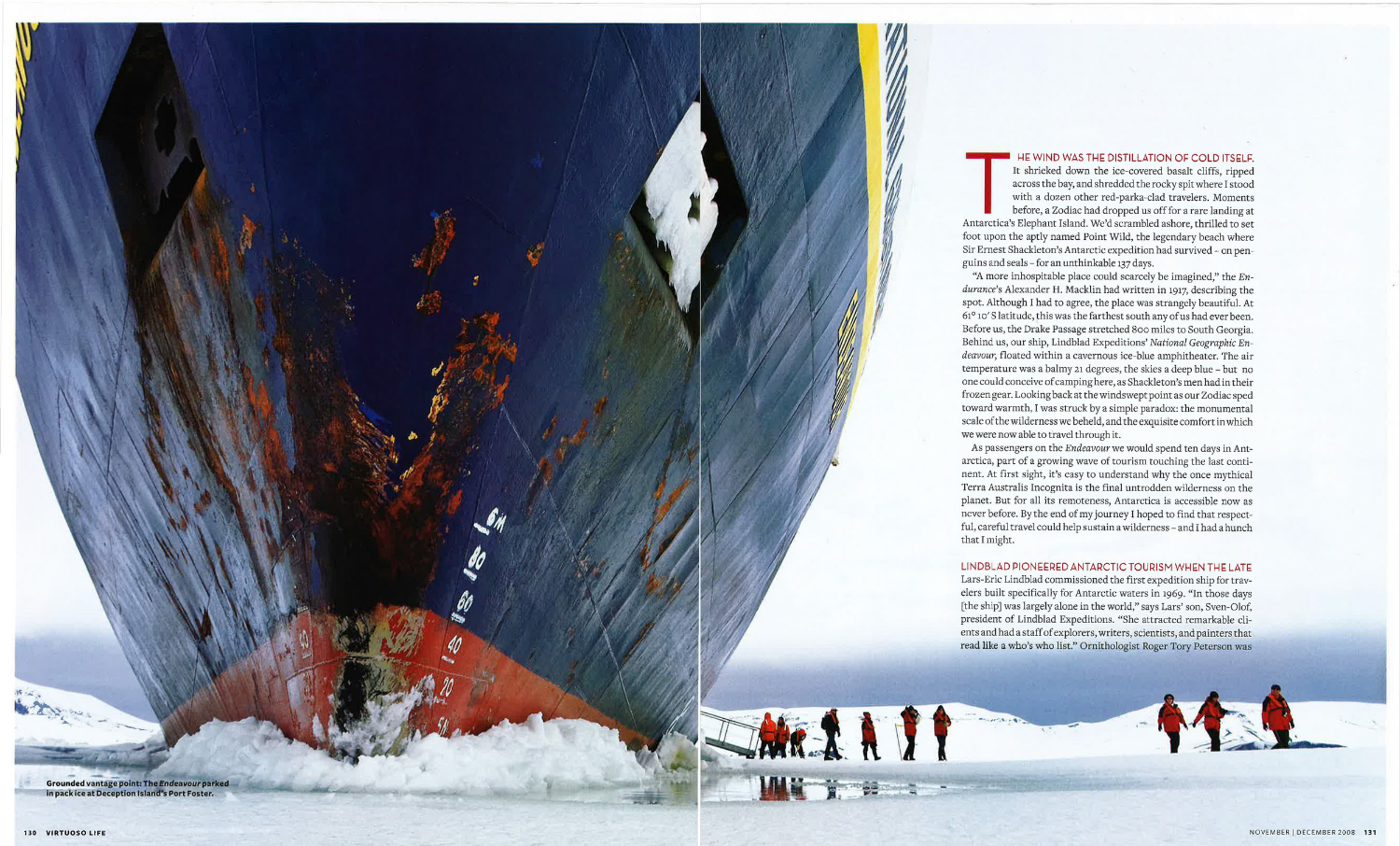

"A more inhospitable place could scarcely be imagined," the Endurance's Alexander H. Macklin had written in 1917, describing the spot. Although I had to agree, the place was strangely beautiful. At 61 ° 10' S latitude, this was the farthest south any of us had ever been. Before us, the Drake Passage stretched 800 miles to South Georgia. Behind us, our ship, Lindblad Expeditions' National Geographic Endeavour, floated within a cavernous ice-blue amphitheater. The air temperature was a balmy 21 degrees, the skies a deep blue - but no one could conceive of camping here, as Shackleton's men had in their frozen gear. Looking back at the windswept point as our Zodiac sped toward warmth, I was struck by a simple paradox: the monumental scale of the wilderness we beheld, and the exquisite comfort in which we were now able to travel through it.

As passengers on the Endeavour we would spend ten days in Antarctica, part of a growing wave of tourism touching the last continent. At first sight, it's easy to understand why the once mythical Terra Australis Incognita is the final untrodden wilderness on the planet. But for all its remoteness, Antarctica is accessible now as never before. By the end of my journey I hoped to find that respectful, careful travel could help sustain a wilderness - and I had a hunch that I might.

LINDBLAD PIONEERED ANTARCTIC TOURISM WHEN THE LATE Lars-Eric Lindblad commissioned the first expedition ship for travelers built specifically for Antarctic waters in 1969. "In those days the shipwas largely alone in the world," says Lars' son, Sven-Olof, president of Lindblad Expeditions. "She attracted remarkable clients and had a staff of explorers, writers, scientists, and painters that read like a who's who list." Ornithologist Roger Tory Peterson was a regular, as was Sir Peter Scott, son of Antarctic explorer Captain Robert Falcon Scott. Climber Tenzing Norgay, naturalist and wildlife painter Robert Bateman, and Keith Shackleton, Ernest's nephew, all sailed with the group.

While Antarctic expeditions have come a long way since then, the spirit of adventure remains. Our Endeavour captain, Oliver Kruess, was making his 72nd Antarctic trip, and our expedition leader, Tim Soper, was backed by 14 well-trained and knowledgeable guides.

I'd rarely felt more alive than when speeding toward Elephant Island - a place most of us had read about, having steeped ourselves in the epic adventures of Shackleton. The reality, however, is that while some of us might love the idea of the heroic age of Antarctic exploration and might dream of sledging across snowy expanses with the likes of Amundsen and Scott, there is nothing better than being able to explore a place like the world's coldest, driest, and windiest continent in measured doses before returning to the welcoming confines of a fully outfitted expedition ship.

Back on board the Endeavour I could slip my toes into sheepskin slippers, pad upstairs to the ship's library, its walls lined with maps and exploration histories, and gaze out at the very landscape through which Shackleton had been drawn. This suited most of us perfectly, as Antarctica is a place that exists not only in geography but also, as the last of the seven continents to be explored, in the terra incognita of our imaginations.

To get there, you basically fly to the end of the world and then keep going. My fellow passengers had met in Santiago, Chile, before catching a flight the following day to Ushuaia, an Argentine outpost at the southernmost tip of Tierra del Fuego. There we boarded the Endeavour and motored east through the Beagle Channel before plunging south for two queasy days across the Drake Passage.

As Captain Kruess informed us over cocktails the first night, his delivery as dry as gin, "Normally we pay a price to get to Antarctica, and that price is the Drake." Sure enough, we felt the first swells of the Southern Ocean around midnight; the 294-foot Endeavour continued to pitch steadily as we progressed through stormy latitudes known as the "Roaring Forties" and "Furious Fifties." While a few passengers were ill enough to stay in their cabins, the vast majority gamely explored the ship, clinging to strategically placed hand-ropes.

Originally built as a North Sea trawler, the Endeavour was converted by Lindblad for expedition cruising in 1998. White with a navy blue hull, she might be taken for a small research vessel - but is home to an elegant dining room, lounge, library, gym, spa, and fleet of12 Zodiacs. Though not an icebreaker, the ship is classed as "ice reinforced," specially designed to withstand rough seas and navigate ice-covered waters. (Icebreakers have strengthened hulls, an ice-breaking bow, and the power to push through pack ice.)

My cabin was tucked at the stern end of the upper passenger deck. It had a single bed with a navy-striped duvet and crisp white sheets, a polished wood bedside table, an upholstered armchair, a closet armoire with drawers, a wooden writing desk, a compact bath with sink and shower, and best of all, two big windows. (One morning I looked out and, to my astonishment, saw a pair of humpback whales swimming alongside.) The ship also has satellite access, which makes it possible to send e-mails home with headings like "Ahoy from Antarctica!" or "Greetings from Elephant Island!"

At 11 AM a day and a half into the Drake, with a stiff wind hurling across the deck and the outside temperature at 29 degrees, we spotted our first iceberg. Up until now, most people had hung along the stern rail, binoculars trained on bands of soaring Cape petrels and wandering albatross. I'd been captivated by the sight of my first albatross, a bird with an 11-foot wingspan. But that thrill paled in comparison to the icebergs. Everyone rushed to the bow or the captain's bridge for an up-close look at the floating sky-blue forms.

The first, a tabular berg sculpted into a massive peak, was as austere and implacable as a church. Its ice was ancient, made of compressed snows laid down centuries ago. Its smooth flanks were dusted with fresh-fallen snow, and where the berg's edges met the sea, the ice revealed itself to be lovely translucent aquamarine. In Barry Lopez's classic, Arctic Dreams, he describes how, for centuries, people searching for a metaphor for icebergs have compared them to cathedrals. "There is a word from the time of the cathedrals," he writes," 'agape,' an expression of intense spiritual affinity." That was it, exactly. I felt agape, spellbound by the sculptural berg's pale light.

After lunch, we donned Wellington boots, waterproof pants, and complimentary expedition parkas for our first shore landing. Our destination: the Aitcho Islands, a small archipelago that is part of the South Shetlands. Speeding across the chilly water, our Zodiacs were surrounded by an otherworldly landscape - jagged snow-covered cliffs plunging into the sea, bright white glacial fields, snow-filled bowls, windswept escarpments. Ashore, the scene was even more surreal: Hundreds of penguins stood in colonies, waiting for the snow to melt so they could build their nests.

We had hardly reached the ice when the penguins began hurrying to greet us. Having evolved in a realm without land predators, penguins have no fear of humans. With their short necks, fused spines, upright stance, and flat stubby wings, they are almost comically inquisitive. I sank to my knees in a snowdrift while birds shaped like footballs marched up and then, with great self-importance, went about collecting stones (or stealing them from their neighbors) for nest-building. There are 18 species of penguins, and on this trip we hoped to see three: the gentoo, the chinstrap, and the Adelie. Of these, only the Adelie, we'd learn, is truly Antarctic, spending its entire life on the continent or close to its shores.

Back on board, spirits were high. "Well, I think we can all agree that was an 'Oh my god!' landing," our trip leader Tim declared in the lounge, where we gathered each evening for drinks and the day's wrap-up.

Part of the Lindblad formula is a daily menu of onboard lectures. My fellow passengers all showed up early for cocktails and sessions such as "The Difference Between Plankton and Krill," "Penguin Copulation," and, especially, "Climate Change." But there was an underlying seriousness; they were a well-traveled, well-educated bunch, eager not only for information about the complexities of global warming, but also for evidence of how it was affecting the icy continent.

They didn't have to look far. Many scientists relate the rise in Antarctic temperatures, especially on the peninsula - which has one of the world's fastest rates of warming - to climate change. Shorelines are emerging as glaciers decline. Chinstrap, gentoo, and other northerly animals, we learned, are displacing animals that depend on year-round ice, such as the Adelies. Near the United States Palmer Station research facility on King George Island, for example, one Adelie colony has gone extinct each year since 1988. Lindblad supports a team of biologists who travel with the company as part of an ongoing penguin study. At some islands' nesting sites they found no Adelies at all.

Although Lindblad's trips tend to have a natural-history focus, most of us had journeyed to the end of the earth to simply experience Antarctica itself. The Endeavour's 110 passengers ranged in age from 22 to 92. An impressive number were visiting their seventh continent. Others told me they'd taken earlier Lindblad expeditions to the Arctic and the Galapagos, and on those trips Antarctica was the place fellow travelers always raved about.

"I feel extraordinarily privileged to be here," one woman confided to me over lunch. "Especially when you consider that among the earth's 6.5 billion people only a tiny fraction will ever experience anything like this."

She had a point. Having always imagined the Antarctic continent as an endlessly flat expanse of snow and ice, I was unprepared for the unearthly beauty of the place. My fellow passengers seemed equally enchanted by the steady sound of the ship's steel hull crunching through pack ice, the giant tabular bergs floating by, the great seaborne ice chunks, snow-covered cliffs, crystalline air, and ever-changing sky. There was something hypnotic, in fact, about the landscape as we moved through it. The biologist David Campbell described it as the antithesis of the Amazon, where everything is teeming with life. In contrast, he wrote, the Antarctic is an environment reduced to the elements, "like the silence between movements of a symphony." It was a

silence in which thoughts had room to roam.

Our days aboard ship took on a predictable rhythm, interrupted only by changes in the weather (there might be brilliant sun one day, screaming wind the second, thick snowflakes the next) and, depending on those conditions, spontaneous shore excursions. One afternoon Captain Kruess pulled the Endeavour up alongside an iceberg so monumental it seemed more of an ice island: the behemoth "B-15D," 25 nautical miles long and five miles wide, which broke free from the Ross Shelf in 2000 and at the time was the largest iceberg ever recorded. In the last seven years it has traveled full circle around the Antarctic continent. Everyone not already on deck or on the bridge grabbed cameras and rushed out to capture not only the looming ice, but the leopard seal lounging on a floe beside it.

Another day we boarded the Zodiacs and sped across windless seas full of gleaming bergs to Deception Island's Baily Head, where 50,000 pairs of chinstrap penguins blanketed the snow, keeping up a constant chatter. The din inside the main crater was deafening, like a concert stadium packed with miniature hormone-crazed teenagers all yakking at once - in black tie. I realized we were lucky not only to be there, but to be there so early in the season - you could only imagine how a place like Baily Head would smell a few months into the nesting cycle. Besides experiencing pristine snow, we were one of only two ships cruising the peninsula; later there would be nearly 50.

"Perhaps the single biggest change in Antarctica is the number of people wanting to experience it," Lindblad naturalist Edward Shaw told me. Forty-five years ago, traveling here was impossible without an oceangoing vessel and a full-fledged expedition. This austral summer nearly 40,000 tourists are expected, compared with just 6,750 during the 1992 to 1993 season. It's hard to visit Antarctica today and not wonder whether we're tipping the balance. The International Association of Antarctica Tour Operators has stringent rules about how many people can be landed at one time, limits on where tourists can go, and more. But not all companies have agreed to join the organization, and in a place with no navy or coast guard, the rules are difficult to enforce.

ON OUR SECOND-TO-LAST DAY AT SEA, we made a shore landing on Petermann Island. We didn't know if the unusually thick pack ice would allow us to even access the shore, so it was with great excitement that we beached the Zodiacs in the soft-falling snow and hiked a short distance to a granite knoll. Here we found our first Adelies, considered one of the bellwethers of Antarctic climate change. Smaller and quieter than either the gentoos or chinstraps, the Adelies seemed at peace, hunkered down in their nests, resolute and cooing softly, further along in the breeding cycle. Brown skua birds zoomed menacingly overhead, making these nests vulnerable in the extreme, but otherwise the scene had a timeless beauty. I knelt down in the snow and stayed there, watching.

A few feet away, one of the Adelies shifted slightly, and that's when I saw it: my first penguin egg. It was luminous - white with a tint of palest blue. It seemed a wonder and a mystery that anything so fragile could survive in this vast, cold place.

Walking back to the Zodiac through centuries of silence, the only sound was my boots crunching through snow. I tried to picture the small round egg, its intense and concentrated grace. It seemed a miraculous thing, as does our planet.

I stepped back into the boat, humbled, and it sped away toward the ship. I thought about the innate beauty of nature and the profound determination of nesting penguins. And I hoped that we, interlopers still on the seventh continent, would deserve it.

_______

By Kim Brown Seely. All rights reserved.